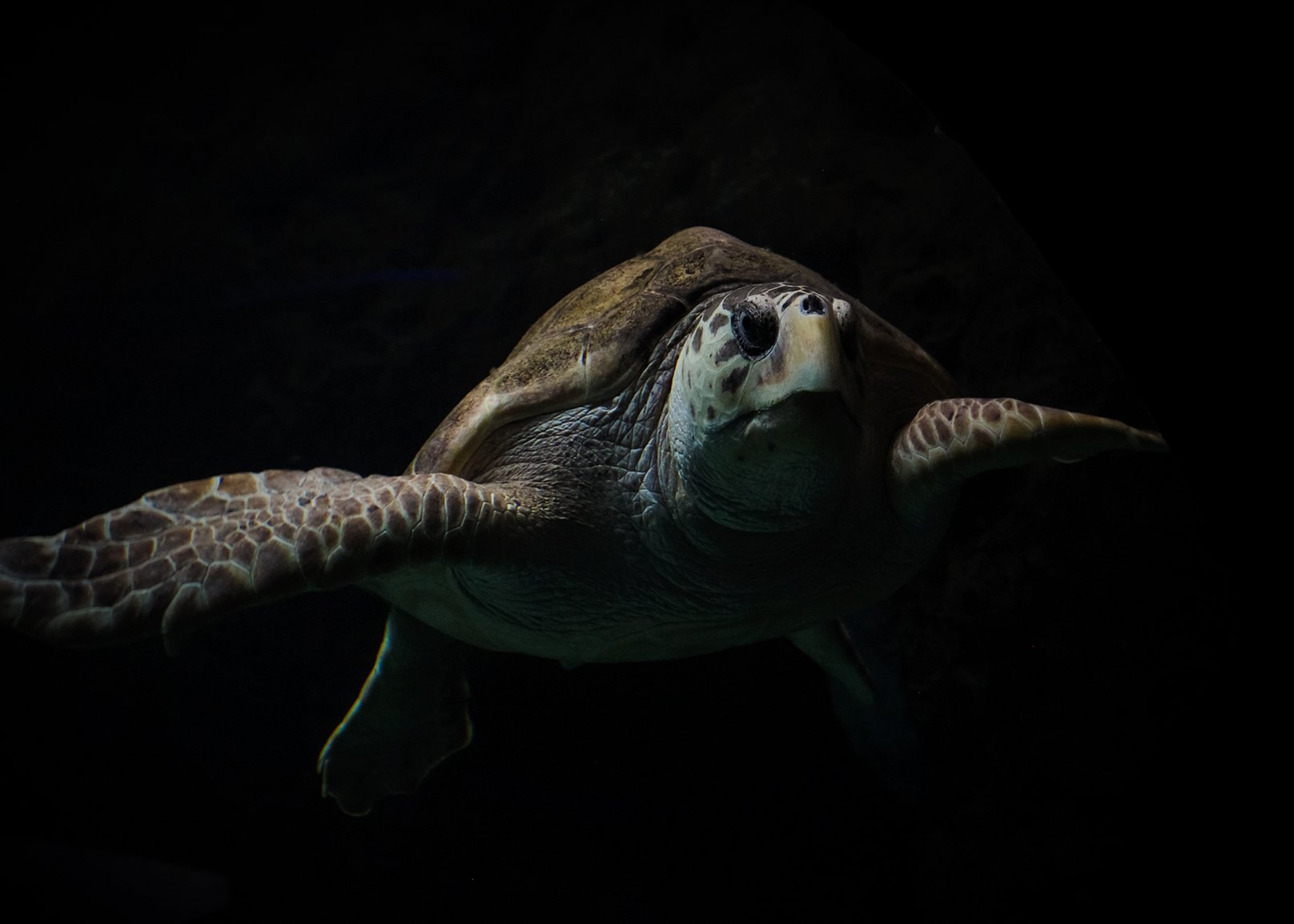

Sea Turtles 101

Atlantic Loggerhead Sea Turtle Facts

MOTHER TURTLES:

Adult females do not begin laying eggs until they are about 30 years old.

Females will not return to land from the time they hatch until they are ready to nest. (Males will not return to land their entire life.)

Females return to the same general beach region where they hatched.

Nesting season may begin after the water temperature reaches 70 degrees (late April/early May).

Mothers typically nest at night, selecting a site in the dunes, hopefully well above the high tide line. They dig a deep hole with their back flippers using alternating strokes and deposit about 120 ping-pong ball size eggs; then cover the nest with sand to hide it from predators.

Nesting is generally in three-year cycles, and females lay multiple clutches 3 to 6 times each nesting season. During nesting season, cycles of egg laying occur about 2 weeks apart.

Early each morning during nesting season, the Sea Turtle Patrol HHI will drive a 14 mile stretch of beach looking for mother turtle tracks from the night before. Upon finding tracks, they use a probe to locate the nest. Next, they mark the nest with 3 poles and tag it with a nest number and enter it in the SCDNR electronic database.

If a turtle lays a nest in a vulnerable location, the Turtle Patrol will transfer that nest to a safer location by hand, but they must move nests within 12 hours of being laid. After 12 hours, each embryo has attached to its shell wall and handling/moving that egg would disrupt development.

IMPORTANT: Following a nesting female with a white flashlight as she makes her way up the beach and/or making loud noises or getting too close will disorient and interrupt her nesting intention. Then it is likely she will return to the ocean without laying her eggs. When a sea turtle crawls ashore and doesn’t lay eggs, scientists call this a “false crawl”.

TURTLE NESTS:

Incubation period is about 60 days, depending on the sand temperature in the nest.

Nest temperature determines a hatchling’s sex: eggs nesting at temperatures above 84.2 Fahrenheit will be female, cooler will be males. A trick to help remember is “Hot chicks/Cool dudes”.

Dangers to nests include raccoons, coyotes, dogs off leash, ghost crabs, and tidal washes.

TURTLE HATCHLINGS:

When the time is right, the hatchlings break through their shell. It can take 2-3 days for the hatchlings to wiggle and dig towards the surface, which often causes a bowling ball size depression in the sand.

Hatchlings will wait for a drop in temperature before emerging from the nest (a boil), which hopefully occurs at night, but boils can happen during the day if clouds/rainstorm cool the air.

A hatchling’s instinct will direct it toward the ocean and then to the Gulf Stream, a 3-day (70 mile) swim. Hatchlings in Florida swim less than 1 day to the Gulf Stream (a mere 5 miles).

The hatchlings have just enough energy to cross the beach and swim to the Gulf Stream. Any distraction or obstacle that wastes this energy will probably spell doom. An additional threat is that hatchlings are food to a wide variety of fish, birds and crabs.

Hatchlings’ internal GPS sets itself when they tumble in the waves, enabling them to return later to their birthplace, navigating the open ocean by the earth’s magnetic field.

One hatchling in a hundred (estimated) actually reaches the Gulf Stream from Hilton Head.

What do adult loggerheads eat?

Because of their powerful crushing jaws, they prefer crunchy sea life like whelk, horseshoe crabs, blue crabs and various other mollusks and crustaceans. However, they also enjoy squishy snacks like jellyfish, sea squirts and sea cucumbers.

Where do loggerheads live?

Atlantic loggerheads stay in the Atlantic, but this species can be found worldwide.

How long do loggerheads live?

It is possible for a loggerhead to live to be 90, but we say with confidence that they live over 100 years. As with all reptiles, they will continue to grow their entire lives, although much more slowly as they age.

An adult can grow up to 4 feet long and can weigh up to 400 pounds.

What dangers do loggerheads face?

Boat propeller strikes, excess fishing line and other debris that can entangle and cause drowning, swallowed fishing hooks, fish net entrapment (shrimp trawlers must now use turtle excluders that allow the turtle to escape from the net), plastics (bags and bottles) mistaken for food and loss of nesting habitat (storm damage, concrete retaining walls, etc.).

Some countries still allow loggerheads or their eggs to be harvested for food.

The only natural predator to an adult loggerhead is a shark.

What can you do to help us protect our loggerheads?

Turn beachfront lights OFF after dark. Sea turtles are phototactic, which means light attracts them. Hatchlings will move toward the brightest light source, traditionally moonlight and stars reflecting off of water to move toward the ocean.

Use only a red beamed light when walking on the beach at night, as white light is distracting and disorienting.

Flatten sand castles, fill holes and remove any obstacles on the beach at the end of each day.

Observe a nesting turtle from a distance.

Touching a nest or hatchling is against federal law, even if hatchling is in distress or not crawling toward the ocean.

Report:

Injured Turtles: Amber Kuehn, Sea Turtle Patrol HHI 843.338.2716

Turtle Code Enforcement Issues (lighting, holes, abandoned beach gear): Town of HH 843.341.4643

Deceased adult turtle (not hatchlings): SCDNR 800.922.5431

FAQs

-

There are several theories as to how they locate this area, but none have yet been proven. The most common theories are:

• The newest theory on how sea turtles navigate is that they can detect both the angle and intensity of the earth’s magnetic field. Using these two characteristics, a sea turtle may be able to determine its latitude and longitude, enabling it to navigate virtually anywhere. Early experiments seem to show that sea turtles have the ability to detect magnetic fields. Whether they actually use this ability to navigate is the next idea being investigated.

• It is widely believed that hatchlings imprint the unique qualities of their natal beach while still in the nest and/or during their first trip from the nest to the sea. Beach characteristics used may include smell, low-frequency sound, magnetic fields, the characteristics of seasonal offshore currents and celestial cues.

• Younger female turtles may follow older, experienced nesting turtles from their feeding grounds to the rookery (breeding site).

-

The nesting process consists of several stages. The female turtle emerges from the sea at night and ascends the beach, searching for a suitable nesting site (somewhere dark and quiet). Once at the chosen nesting site, she begins to dig a body pit by using all four flippers. She removes the dry surface sand beneath her, which will later be used to cover the egg chamber. Once she has created a body pit, she begins to dig an egg chamber using her rear flippers, alternating between the right and left flipper to scoops out the damp sand. When she can reach no deeper, she pauses and begins contractions, her rear flippers rising off the sand. Soon she begins laying eggs. Following each contraction, the female turtle will drop between one and four eggs in quick succession. The eggs will almost fill the chamber. Once her clutch is complete, she closes the nest using her rear flippers in a similar way to digging her egg chamber, just in reverse. She places sand on top of the chamber, until the eggs are completely covered. She gently pats the damp sand on top of her eggs, using the underside of her shell (plastron). The camouflaging process now begins. Slowly moving forward, she throws dry, surface sand behind her. This is an effort to conceal the location of her eggs from predators. She may move forward while she is doing this. When she is done, she heads down the beach and returns to sea.

-

The number of eggs in a nest, called a clutch, varies by species. In addition, sea turtles may lay more than one clutch during a nesting season. On average, sea turtles lay 110 eggs in a nest, and average between 2 to 8 nests a season. The smallest clutches are laid by Flatback turtles, approximately 50 eggs per clutch. The largest clutches are laid by hawksbills, which may lay over 200 eggs in a nest.

-

They are the size and shape of ping-pong balls with a soft shell. Usually eggs are spherical in shape, although occasionally, they are misshaped (elongated or adjoined with calcium strands). Some sea turtles lay small infertile eggs, which only contain albumin (egg white). The Leatherback turtle lays some of these infertile eggs in every clutch, but the other species of sea turtle lay these eggs infrequently.

-

The temperature of the nest determines a hatchling’s gender. This is called Temperature-Dependent Sex Determination (TSD). Warmer temperatures produce mostly females, and cooler temperatures produce a majority of males. There is a pivotal temperature that produces an equal ratio of males and females. The temperature determining sex ratio differs between species and nest locations.

-

No. Once a nest has been completed, the female never returns to it. The eggs and resulting hatchlings are left to fend for themselves and locate the water upon emerging.

-

Because hatchlings are small and the egg chambers are deep, it is almost impossible for a single hatchling to escape from the chamber alone. As hatchlings break free from their shell inside the egg chamber, they stimulate other hatchlings to emerge from their eggs too. Once most hatchlings have emerged from their shells, they climb on top of the discarded eggshells to propel themselves to the top of the chamber. The hatchlings near the top of the egg chamber scratch down sand from above and around them. They emerge either en masse or in small groups. Emerging together increases the chance of survival as many hatchlings can overwhelm would-be predators. A single hatchling would be an easy target.

-

The difference in number is based on whether or not the black sea turtle is a separate species from the green sea turtle. The debate centers on the genetic difference between the green sea turtle and the black sea turtle. Most sea turtle researchers believe that the black sea turtle should be called the Pacific green turtle because it is a sub-species of the green sea turtle and, as a result, has almost identical genetic traits. Some sea turtle researchers believe that the physical characteristics and other behavioral difference indicate that it should be classified as its own species.

-

Sea turtles are “phototactic,” meaning that they are attracted to light. They are guided by the brightest light, which is usually moonlight reflecting on the sea. Turtles avoid shadows, including dune vegetation at the top of the beach, places where danger could lie.

-

Each species feeds on a diet specific to that species. For example, loggerheads feed mainly on hard-shelled organisms such as lobsters, crustaceans, and fish. Green turtles prefer sea grasses, while leatherbacks feed primarily on jellyfish. Hawksbills have a hawk-like beak that is used to cut through tough coral, anemones and sea sponges. Loggerheads have powerful jaws that crush shellfish and mollusks. Although green sea turtles’ jaws are serrated, all sea turtles’ jaws lack teeth. The leatherback’s jaw has 2 prominent ‘cusps’ on the upper jawbone, distinguishing it from the other turtles.

-

Leatherbacks can dive to a depth of more than 1,000 meters (3,000 feet) in search of their prey, jellyfish. The hard-shelled species dive at shallower depths. The leatherback is adapted to deep dives because of its unique morphology. Unlike other sea turtles, the leatherback lacks a rigid breastbone that allows it to collapse during deep dives. There is a large amount of oil in the skin and the leathery shell absorbs Nitrogen, reducing problems arising from decompression during deep dives and resurfacing.

-

As sea turtles are air breathing reptiles, they need to surface to breathe. Sea turtles can hold their breath for several hours, depending upon the level of activity. A resting or sleeping turtle can remain underwater for 4-7 hours. Recent research has shown that some turtles can even hibernate in the sea for several months! However, a stressed turtle, entangled in fishing gear for instance, quickly uses up oxygen stored within its body and may drown within minutes.

-

The largest species of sea turtle was the Archelon, which measured 7 meters (about 21 feet) in length and lived during the time of the dinosaurs. Today, the largest living species is the leatherback turtle. Atlantic leatherbacks are slightly larger than the Pacific population. Leatherbacks measure, on average, 2 meters (6 feet) in carapace (shell) length. The largest leatherback ever recorded was a male found stranded on the Welsh coast in 1987. He measured almost 3 meters (9 feet) from tip to tail and weighed 970 kg (2,138 lbs).

-

Researchers track sea turtles through using satellite telemetry. A small transmitter is attached to the turtle’s carapace (on hard shelled species) or on a leatherback using a harness that resembles a backpack. The transmitter emits signals of information to an orbiting satellite when the turtle surfaces to breathe or bask. The information in the signals is sent to receiving stations on Earth, and is then sent to the researcher’s computer as a dataset. This data provides information on the turtle’s location, number of dives during the last day, length of the most recent dive, water temperature, etc. Data, received over a period of time, allows for tracking a turtles movement patterns and swimming speed. Usually, satellite transmitters are attached to females that come ashore to nest. Tracking has provided important information on migration routes between breeding and foraging (feeding) habitats. The time length of tracking depends upon how long the device remains on the turtle and on battery life. Tracking usually continues for 6-10 months, although cases have been reported exceeding 2 years. After about two years, the transmitters fall safely off the turtles.

-

There are three primary methods of tagging sea turtles. Flipper tags are made of metal or plastic and are clipped onto the turtles’ flipper(s). These tags are clearly visible, each containing a unique serial number and the address of the organization applying the tags. There also are tags called Passive Integrated Transponder tags or “PIT tags.” These are microchips that are injected into the turtles shoulder muscle, the area of the flipper closest to the shell. Each PIT tag also has a unique digital serial number and requires the use of PIT scanning equipment to display the tag number. While PIT tags are more secure than flipper tags, their higher cost and the need for specialized equipment limits many researchers from using them.

-

Sea turtles are tagged for several reasons. Flipper and PIT tags are used to identify individual turtles to help researchers learn things like nesting site fidelity, the number of nests laid during a nesting season, the number of years between nesting seasons, and growth rates. In addition, these tags can be used to identify where a captured or stranded turtle was originally tagged, which can be used to establish possible migration pathways. While flipper and PIT tags can provide starting and ending points for migration, satellite tags are able to provide research and conservationists with the actual routes that sea turtles take between different habitats.

-

For the eggs to survive and have a chance of hatching, sea turtles must lay their eggs on sandy beaches. As they are developing, the embryos breathe air through a membrane in the eggs, and so they cannot survive if they are continuously covered with water. If disturbed, sea turtles will sometimes nest. They will return to sea and usually try to nest again elsewhere later that night or within a couple days. Once a clutch of eggs is ready to be deposited, the female must deposit them to allow development of another clutch of eggs. While it is very unusual, turtles disturbed during different nesting attempts may release their eggs in the sea if they can’t carry them any longer. Captive turtles have been known to drop eggs into the water.

-

The most common species of sea turtle is the Olive Ridley, with an estimated 800,000 nesting females. The most endangered is the Kemp’s Ridley, with an estimated 2,500 nesting females (though nesting numbers have been increasing over the past 10 years).

-

Sea turtles once navigated throughout the world’s oceans in huge numbers. But in the past 100 years, human demand for turtle meat, eggs, skin and colorful shells have reduced their populations. Destruction of feeding and nesting habitats and pollution of the world’s oceans are all taking a serious toll on remaining sea turtle populations. Many breeding populations have already become extinct, and some surviving species are being threatened to extinction. Sadly, only an estimated one in 1 to 1,000 will survive to adulthood. The natural obstacles faced by young and adult sea turtles are staggering, but it is the increasing problems caused by humans that are threatening their future survival.

-

There are two major ecological effects of sea turtle extinction:

1. Sea turtles, especially green sea turtles, are one of the very few animals to eat sea grass. Like normal lawn grass, sea grass needs to be constantly cut short to be healthy and help it grow across the sea floor. Sea turtles and manatees act as grazing animals that cut the grass short and help maintain the health of the sea grass beds. Sea grass beds are important because they provide breeding and developmental grounds for many species of fish, shellfish and crustaceans. Over the past decades, there has been a decline in sea grass beds. This decline may be linked to fewer numbers of sea turtles grazing. Without sea grass habitats, many of marine species would be lost. All parts of an ecosystem are important. If you lose one, the rest will eventually follow.

2. Beaches and dune systems do not retain nutrients well because of the sand, so very little vegetation grows on the dunes and no vegetation grows on the beach itself. Sea turtles use beaches and the lower dunes to nest and lay their eggs. Sea turtles deposit an average of about 100 eggs in each nest and lay between 3 and 7 nests during the nesting season. Along a 20-mile stretch of beach on the east coast of Florida, sea turtles lay over 150,000 lbs of eggs in the sand. Not every nest will hatch, not every egg in a nest will hatch, and not all of the hatchlings in a nest will make it out of the nest. The unhatched nests, eggs and trapped hatchlings are good sources of nutrients for the dune vegetation, even the left over egg shells from hatched eggs provide some nutrients. As a result, dune vegetation is able to grow and become stronger with the presence of nutrients from turtle eggs. As the dune vegetation grows stronger and healthier, the health of the entire coastal ecosystem becomes better. Stronger vegetation and root systems helps to hold the sand in the dunes and helps protect the beach from erosion. If sea turtles become extinct, dune vegetation would lose a major source of nutrients and would de-stabilize the ecosystem, resulting in increased coastal erosion and reduced habitat for wildlife. Once again, all parts of an ecosystem are important, if you lose one, the rest will eventually follow.

Sea turtles are part of two ecosystems, the coastal system and the marine system. If sea turtles became extinct, both the marine and coastal ecosystems would be negatively affected. And because humans utilize the marine ecosystem as a natural resource for food and use the coastal system for a variety of activities, a negative impact to these ecosystems would negatively affect humans.

-

There has not been a turtle followed from emergence to natural death, but based on the information we have it is assumed that sea turtles can live 60 or more years depending on the species. Onset of sexual maturity is also species dependent, but researchers believe that it is around 20‐30 years for loggerheads. (Source: SCDNR)

-

As hatchlings or juveniles, you can't tell by looking. As adults, males have a much longer tail than females, and a more pronounced curved claw on each front flipper. Sand temperature affects gender: 29.6°C during the middle third of incubation will produce a 50:50 gender ratio. A couple of degrees higher will produce all females and a couple of degrees cooler will produce all males. (Source: SCDNR)

-

Nobody knows for sure, but recent research suggests that about 1 in 1000 hatchlings will make it to adulthood. (Source: SCDNR)

-

It isn’t entirely known because there are very few observations of sea turtles between the stages of hatchling and “dinner‐plate” size. Once they reach this size, they are seen in the waters around Cape Verde, Canaries, Azores, and Madeira Islands. It is assumed that before arriving there the small turtles float passively along major North Atlantic currents, near the Sargasso Sea. (Source: SCDNR)

-

Birds, mammals and fish are the primary predators. One of the reasons that sea turtles emerge at night is to avoid predation from predators that are diurnal. (Source: SCDNR)